What We Can Learn from Orwell’s Rules for Great Writing for Effective Communication with Patients

Originally published by Leigh Kendall – 5th September 2019

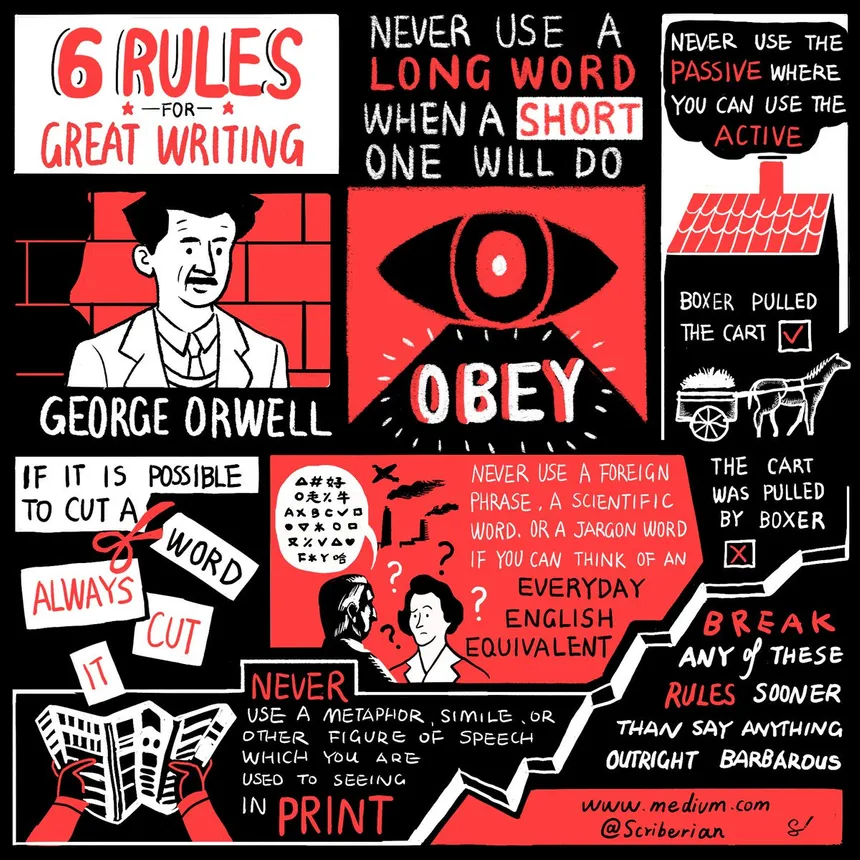

Recently I came across this sketchnote by Scriberia detailing the author George Orwell’s Rules for Great Writing. Orwell’s rules are a useful guide for anyone, especially those who write for a living, to ensure text is clear, concise, and easily accessible by the reader. (Note I prefer the word ‘guide’ rather than ‘rules’!).

Seeing the rules in sketchnote form popped a lightbulb in my head – the ‘rules’ are a useful guide for communicating with patients and families, especially:

- Not using a long word when a short one will do

- Not using a scientific word, jargon, or a foreign phrase where there is an English equivalent.

Most people who have been at the receiving end of care will appreciate how confusing it can be to be faced with a range of unfamiliar words and phrases. Many medical words use words that we don’t recognise or use in everyday plain English, and are a mouthful with their many syllables (and we’re often unsure how to pronounce them).

The long complicated words can create a barrier between a health care professional and a patient. The NHS has a focus on personalising care, which is about giving people greater control about how and where their health and care is provided. Improved communication improves understanding, which in turn can improve the level of control a person has over their care, resulting in better outcomes for that person.

In addition, the practice of sending a letter to a patient after an appointment with a consultant as described in a BMJ article means “Having to gather one’s thoughts to construct a letter that is readily understood, informative, and educational reinforces the role of the doctor as educator and helps focus the discussion on the issues that matter most to the patient.”

So, wherever possible it’s best to use a plain English equivalent rather than the ‘proper’ medical word, acronyms, and jargon. As the BMJ article also mentions: “The letters need to be easily readable, which can be measured using measurement tools such as the Flesch Reading Ease score.”

The BMJ article, with its recognition of the importance of patient communication, is a really heartening read.

With other written communication such as information leaflets there can be so much text it can feel overwhelming – and often the parts the reader really needs to know can get lost. This is where the ‘rule’ about cutting words wherever it is possible to do so comes in.

When my son was born very prematurely, I was given a stack of very wordy leaflets and booklets. Similarly wordy leaflets were provided after my son sadly died. All were provided with the best of intentions, but due to the level of detail were ultimately useless.

That’s why I created bereavement cards that doctors could give to parents after their baby has died. The doctors say the cards have been a huge help to them as they are able to give parents a tangible piece of useful information, and they say the parents have given feedback to say they found the card invaluable in navigating those awful raw early days when it feels like your world has literally come to end. Anything that can help at that time is a huge comfort.

One size will never fit all, of course; everyone has their own individual needs, and as Orwell said we should break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous!

Let’s make sure communication in health care helps and supports, rather than hinders.

You may also be interested in: